By Gelareh Darabi

I had always been skeptical of global international environmental conferences like COP or World Summits. From an outside perspective it seemed like a carbon intensive gathering that produced little in terms of major accords or global commitments. What I didn’t realize was how powerful it is for people to gather. We are social animals after all, and even though large scale unilateral binding agreements aren’t often achieved, what happens in the hallways, front steps, and side stages is irreplaceable. These micro moments and connections are too fleeting to be reported out to the larger world who are keeping an eye and wondering, like I always did, “what’s the point of all this again?”

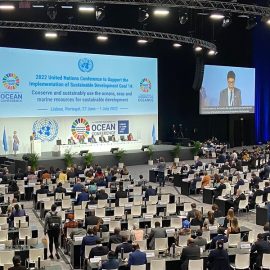

The second UN Ocean Conference took place at the beginning of July in Lisbon, Portugal. The last time ocean protectors had gathered was five years ago in New York – so much had changed since then. For one, the pandemic not only kept us physically apart from one another, but the global health crisis that is covid-19 also revived a fading plastics industry and put new pressure on the ocean as disposable masks and gloves soon began washing up on beaches around the world. For those who have been fighting to have the ghost gear and marine litter crisis front and centre, like Joel Baziuk from The Global Ghost Gear Initiative, the past five years have felt like a “watershed moment.”

For the longest time, the conversation around marine plastic seemed mostly focused on the Great Pacific garbage patch, a curious Bermuda triangle of waste that is hard to comprehend, and in many ways is out of sight and out of mind. This time round, marine plastics, microplastics and ghost gear were key topics of discussion and debate, not just amongst those who have dedicated their life’s work to ocean health, but also to the everyday consumers who are starting to get excited about the idea of circularity, as so many beautiful products and innovations have come out of marine waste.

This was another key group of contributors at this year’s conference, the designers and architects of these beautiful products that are inspiring people to consciously spend with ocean health in mind. Not only have we closed the production loop on marine waste, but in many ways the presence of the design and innovation sector at this event, closed a representation loop, as all circular stakeholders had a seat at the table. We’re now at a place where policymakers and creatives actually have a common interest and language, not just from an environmental perspective, but an economic one as well. Head of the Unit Maritime Innovation, Knowledge and Investments at European Commission DG Mare, Andreea Strachinescu, feels so much more can be done from the business sector when it comes to circularity. In her eyes, A circular blue economy can’t thrive without investments in restoration in marine and freshwater ecosystems.

“In order to take full advantage of what the ocean can offer us, we need to know it, respect it and use it in a sustainable way.”

These kinds of strides in the business sector were apparent in the green venture capital firms who not only showed up, but who made significant investments in both scientifically backed and heavily researched tech like unmanned vessels traveling out to sea for months on end to collect key data on microplastics to more practical items like a beautiful designed cooler made from a prevalent type of waste – coconut husks!

Unfortunately, one major community who didn’t have a significant seat at the table were global fishers. This observation was echoed by Healthy Seas collaborator Lefteris Arapakis, co founder of Enaleia. He felt it seemed “undemocratic” to have this high impact community absent from the larger conversations, especially as so many of the decisions that come out of these events directly impact their livelihoods and families. It was exactly the scientific innovations that had fishing communities in mind that had me the most excited, including satellite trackers that could be placed on fishing nets when they are first acquired, so should they be lost on the job, they could be located and retrieved so much easier. This not only helps the fishers who are gaining a key and expensive part of their tool kit, but the volunteer divers who are often the first to be contacted to help retrieve the nets.

Ultimately, attending the UN Ocean Conference made me increasingly appreciative of the frontline work that Healthy Seas does, not only dialoguing with stakeholders of the fishing sector, but alerting the global community of hotspots and concerns in the enormous challenge that is tackling ghost gear. It is thanks to the work by organisations like Healthy Seas that the issue of ghost fishing was at the frontline of this high impact global conference this year.

Tune in to the podcast

Gelareh Darabi is an environmental journalist (National Geographic, AJ+), documentary filmmaker and Healthy Seas Ambassador.

What many people don’t know about her is that she started her career in journalism as a fashion reporter, but once she had the personal breakthrough that she had a real interest and knack in science and environment storytelling, she kind of buried this part of her biography. It wasn’t until she made a film about Healthy Seas and the rise of sustainable fashion that she started to see the value in her experience covering the fashion industry.

Once she started investigating fast fashion and the environmental destruction brought about by our throw away culture, she really became passionate about this issue. She committed to only wearing sustainable brands on-camera which trickled into her everyday life as she began “greening” her wardrobe, cosmetics and lifestyle. She say’s it’s a work in progress, but something she’s passionate about sharing.

Follow Gelareh on Instagram